Ever since the collapse of the USSR, the Russian authorities have argued repeatedly that the country needs a unifying national idea. But it was only after the annexation of Crimea in 2014 that, for the first time in post-Soviet history, the notion of drawing up legislation on state ideological policy was mooted, along with the possibility of introducing amendments to the constitution that would allow this. Although the Kremlin has not yet built up a well-constructed narrative and continues to draw on symbols from different historical periods, its efforts suggest a readiness to revive ideological dogmas. Rhetorical trends in statutes and other state documents, as well as in staffing policy and the official politics of memory, reveal the increasingly totalitarian nature of Russian society.

Patriotism as state ideology

In February 2016, Vladimir Putin announced that patriotism was to be equated with the Russian national idea. Subsequently, the leader of the parliamentary party ‘A Fair and Just Russia’ (Spravedlivaya Rossiya), Sergei Mironov, declared that the constitutional norm prohibiting the establishment of a state ideology ‘no longer corresponds to national interests’. He was supported by the ombudsman, Tatyana Moskalkova, who expressed the view that a debate about removing the prohibition on state ideology from the constitution could be justified.

At the end of October 2016, it was suggested at a meeting of the Presidential Council for Inter-Ethnic Relations that a law on the Russian nation should be drawn up. This was supported by Putin. Mironov called this initiative the first step in the ‘tangible creation of a state ideology’. The speaker of the Federal Council, Valentina Matvienko, also emphasised that Russia needs a national idea founded on patriotism. At the beginning of December, Putin instructed the presidium of the Council to draw up a draft law before 1 August 2017.A parliamentary commission was duly set up.

The Kremlin’s ideological motives

This ideological trend became better established after the annexation of Crimea and the start of Russian military aggression in south-eastern Ukraine in 2014.

When the Euromaidan protests began in the autumn of 2013, the Putin regime was experiencing a crisis of legitimacy. Its level of popularity had reached the lowest level since 2000. The annexation of Crimea and the huge propaganda campaign that followed helped the Kremlin to regain the support of the population.

This was by no means the first time, under Putin’s governance, that the achievement of greater social cohesion had been sought through military conflict and confrontation with the West. Support for the president had reached its highest, post-Crimean level in 1999, 2003–4 and 2008. In each case, this occurred against the backdrop of military action and a confrontation with the EU and the USA on Serbia, Iraq, Georgia or Ukraine. All these campaigns also exploited anti-western motifs ‘combining a rhetoric of mass resentment, patriotism and revenge.’

But the propaganda campaign launched on state television simultaneously with military action in Ukraine proved unprecedented in its ferocity and aggression. Over the course of two months, Putin’s ratings rose by 20 percentage points – from 65 per cent in January 2014 to 87 per cent in March. Simultaneously, there was a turnabout in public attitudes towards European countries and the United States. According to data released by the Levada Centre, in January 2015 the proportion of people taking a negative view of the European Union reached a record 71 per cent, while those ill-disposed to the USA counted 81 per cent. Yet in March 2011, for example, 62 per cent of Russians had been favourably disposed to the EU, and 54 per cent took a positive view of the USA.

From then on, the Putin regime – which had effectively put the county on a military footing – regarded foreign policy as the chief means by which greater internal social cohesion could be achieved. As the sociologist Lev Gudkov explained at the time, Putin’s speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2007 had already given Russian foreign policy ‘the features of a geopolitical mission’, with its fervent message to a West dubbed ‘infirm and in its declining years’, with a lost sense of tradition and morality. This approach was consolidated when Putin returned to the Kremlin in 2012, and especially after the annexation of Crimea: ‘Thanks to the strength of the national spirit, the preservation of Christian values and a powerful and renovated army, Russia has been reborn as a “great power … It has its own interests and a right to power legitimated by its time-honoured contribution to the welfare of the nations of Europe, which it liberated from fascism.’ In a separate interview, Putin boasted that ‘We are stronger than anyone, because we are in the right. Power lies in truth. When a Russian has a sense of his own righteousness, he is invincible.’

The post-Crimean campaign became marked by the fact that, in addition to advertising the idea of a traditionally ‘hostile’ West, the Russian authorities began to promote a very distinct image of western Europe as a source of alien values and a hotbed of amorality. The campaign’s objectives permitted the state – along with the Orthodox Church which traditionally also harbours anti-western and anti-liberal views – to intervene further in the private lives of Russia’s citizens, so consolidating ‘conservative’ values. The newest example of this has been a law on the decriminalisation of domestic violence, ratified by the president on 7 February 2017.

The erosion of support for the Putin regime became apparent in the mass demonstrations in 2011–12, held in protest against the falsification of the elections and the return of Putin for a third presidential term. This prompted the authorities to declare war on representatives of civil society who opposed them. It is no coincidence that the strategy for the national security of Russia, sanctioned by presidential decree at the end of 2015, highlights ‘the activity of foreign and international non-governmental organisations among the fundamental threats to the security of the state and Russian society’. Other threats cited included ‘financial and economic bodies and individuals seeking to destabilise the internal political and social situation in the country, to provoke “coloured revolutions”, and to destroy traditional Russian spiritual and moral values.’

The allegation that the protest movement is a conduit for the anti-Russian interests of the West has become the main way of discrediting it. Since 2012, Russia has introduced dozens of repressive laws curtailing the constitutional rights and freedoms of its citizens. These include the law on non-commercial organisations, ‘foreign agents’, and the law on treason, which have revived the anti-western rhetoric of the Cold War. Following the annexation of Crimea, the demonization of dissenting voices reached its peak, with them being openly dubbed ‘fifth columnists.’ At the beginning of March 2014, Putin declared that ‘some western politicians are not only threatening us with sanctions, but with the prospect of increasingly acute internal problems. It would help to know what exactly they have in mind: the activities of some kind of fifth column – various “national traitors”.’Federal TV channels broadcasted a string of films discrediting dissenters.

The official politics of memory

The appeal to patriotic feeling and a ‘national idea’ has caused the past to take on increased significance in legitimising the regime. On the one hand, the authorities have sought to demonstrate a continuous link with centuries of Russian history, emphasising the need for reconciliation and national unity; on the other, they have expressed their intention to actively resist any attempt to reflect critically on the past or offer an alternative interpretation of historical events.

The tendency noted above is clearly evident in the official statements issued as the centenary of the 1917 revolution approaches. They come over like a series of carbon copies. ‘We must learn the lessons of history for the purposes of reconciliation, and to consolidate the social, political and civic concord we have achieved to date. It is unacceptable […] to speculate on tragedy in the interests of personal, political – or other – gain,’ declared Putin in his annual address to the Federal Assembly on 1 December 2016. ‘The memory of these terrible events should not become an additional source of division in our society,’ the parliamentary speaker of the Russian Federation, Vyacheslav Volodin, said at the beginning of January 2017.

Meanwhile, the chairman of the committee of the Federal Council for defence and security, Victor Ozerov, has warned that: ‘Many members of the unofficial opposition will seek to draw parallels between 1917 and today, in order to say that a similar revolution could take place even now.’ The author of an outrageous package of anti-terrorist laws brought into force on 20 July 2016 claimed that, ‘According to “orange” spin doctors, the year “2017” is to be associated with revolution and used as a political pointer to provoke social schism. That is why the possibility of historical falsification and subversive interpretations of history cannot be excluded.’ These anti-terrorist laws introduced criminal prosecution for failure to report a crime and enabled children aged 14 to be tried in court.

Earlier, in May 2015, at a round table of the Russian society for military history, entitled ‘A Hundred Years of the Great Russian Revolution: an interpretation for [social] consolidation’, the minister of culture, Vladimir Medinsky presented a series of ‘theses on behalf of the platform for national reconciliation’ linked to the forthcoming anniversary. It was the minister’s view that peace could be achieved through ‘an acknowledgement of the continuous line of historical development from the Russian Empire, through the USSR, to the contemporary Russian Federation’; through ‘recognition of the tragic nature of social division’; ‘a condemnation of the ideology of revolutionary terror’; and through ‘an understanding of the error of counting on foreign “allies” in the resolution of internal political disputes’.

From the point of view of the state authorities, the forthcoming anniversary does not call for any interpretation of the causes and effects of the 1917 revolution. Instead, judging by what we have seen to date, it will be used to legitimise and stabilise the regime.

Given the potential power of history to consolidate the community, the Kremlin indefatigably and insistently demands a ‘correct’ attitude to the past. A plan for state cultural policy to 2030, ratified by the government in March 2016, categorises ‘the corruption of historical memory, the negative assessment of significant periods in the history of the fatherland, [and] the dissemination of a false view of the historical backwardness of Russia’ as ‘manifestations of a humanitarian crisis that could have the most dangerous possible effect on the future of the Russian Federation’. According to the Russia’s new Information Security Doctrine ratified by presidential decree in December 2016, it is essential ‘to neutralise the psychological effects of information that seeks to undermine the historical foundations and patriotic traditions linked to the defence of the fatherland’.

The real purpose of the state’s war against the falsification of history is to suppress any urge to interpret the past critically, and to prevent criticism of the Soviet leadership or the condemnation of Soviet crimes.

The law prohibiting ‘the rehabilitation of Nazism’ introduced into the Criminal Code in May 2014 appears to be designed to resolve these issues.The first guilty verdict based on this legal article was passed by the Perm regional court on 30 June 2016 and convicted a metal worker, Vladimir Luzgin, for linking on his social media account to an article which, according to the decision of the court, ‘contained information about the activities of the USSR at the time of the Second World War, which is known to be false. That is to say the statement that [the war] was unleashed by communists (i.e. the Soviet Union) together with Germany.’ In the view of the court this information contradicts ‘the facts established in the sentence passed by the Nuremberg Tribunal’.

While constantly insisting that the falsification of history is unacceptable, the authorities themselves actively contribute to the myth-making process. Nor do they balk at downright forgery – as in the case of their handling of the legend of Panfilov’s 28 Men. This story of a group of heroic guardsmen who supposedly saved Moscow in the winter of 1941 was exposed as inaccurate back in 1948 by the Chief Military Office of the public prosecutor of the USSR. Today it is once again being jealously protected – lest it be debunked – and deliberately sacralised. In March 2016, the director of the State Archive, Sergei Mironenko, was forced to retire soon after calling the story of the heroic achievement of the Panfilov’s 28 Men a myth. In the autumn of 2016, Minister of Culture Medinsky declared that Panfilov’s 28 Men was ‘a sacred legend which must not be touched, and the people who do so are utter scum’.

Minister Medinsky is also the head of the Russian Society for Military History (RVIO), founded at the end of 2012 following a decree issued by President Putin ‘to help promote the study of the military history of the fatherland; to challenge any attempt at distorting it; to ensure the popularisation of the achievements of military history as an academic discipline; and to encourage patriotic education and increase the prestige of military service’. Alongside implementing the cultural policy imposed by the state, the RVIO is also involved in raising monuments, establishing museums and publishing books (including a history of Crimea and of Novorossiya). It also finances and produces films on historical and patriotic themes (e.g. the film ‘Panfilov’s 28 Guardsmen’).

In addition to using propaganda and administrative resources to advance official policy on the uses of memory, the Russian authorities systematically block the opening of archives and the publication of information about the Soviet era. They are also increasingly persecuting academics who work on the history of Soviet repressions or who offer interpretations of historical fact that are ‘incorrect’ from the point of view of the state. For example, in mid-December 2016, the historian Yurii Dmitriev was arrested in Petrozavodsk under extraordinarily bizarre circumstances. Dmitriev is also a political activist, the head of the Karelian regional office of ‘Memorial’, and an originator and founder of the Sandarmokh memorial complex. He is threatened with up to 15 years imprisonment. His friends and colleagues consider his arrest to be an act of reprisal following Dmitriev’s sustained efforts to record the names of people persecuted during the years of Stalinist terror, and their oppressors.

The rise of the Stalinist myth

It is worth noting that in the context of this ideological turnabout, the figure of Stalin has become increasingly prominent both in the official politics of memory, and in Russian public consciousness. For the present, the authorities are not glorifying Stalin openly, but their policies and rhetoric contribute to the growth of the Stalinist myth.

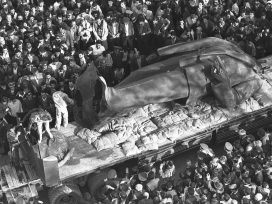

In 2015–16, Ukraine was taking down monuments to Lenin and other Soviet leaders. Meanwhile in Russia, where thousands of Soviet statues of Lenin remain standing, dozens of additional, new monuments to Stalin have also been raised. Although most of these were erected by communists with the connivance or support of local authorities, some were unveiled in the presence of officials of the highest rank. In February 2015, the chairman of the State Duma, Sergei Naryshkin, was present at the unveiling, in Yalta, of a group sculpture representing Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill, in commemoration of the jubilee of the meeting of the ‘Big Three’ in 1945. And in July 2016, in the village of Khoroshevo in the Tver region, the RVIO raised a monument to the generalissimo near the house where Stalin stayed during his trip to the front on 4–5 August 1943. The minister of culture and head of the RVIO, Vladimir Medinsky, was present at the unveiling ceremony.

State propaganda increasingly links the figure of Stalin to the USSR’s victory in the Great Patriotic War. This remains the cornerstone of collective memory, and a major source of national pride in Russia. (In a poll conducted in March 2016, 71 per cent of respondents agreed that’ whatever errors and vices may have been attributed to Stalin, the most important fact is that, under his leadership, our nation emerged victorious in the war.’)

Furthermore, an average Russian receptive to state propaganda will feel it is important that military success broadened the USSR’s sphere of influence, forced the world to ‘take account’ of it, and helped it to gain the status of a world power. The Kremlin also skilfully exploits the rhetoric, language and symbols of the Second World War in the new wars it is waging in Ukraine and Syria. Contemporary military operations are presented as ‘holy wars’ – battles between good and evil – in which Russia is the absolute force for ‘good’, just as it was when it confronted Hitler’s fascism.

Stalin is useful to the Russian regime because, as a figurehead, he shrouds ideas about a world power, imperial expansion and a great nation, as well as notions of the uncontrollability of the authorities and their unaccountability to the public. The image of the ‘Leader’ gives positive representation to the priority of the state’s objectives over personal interests. It legitimises the use of violence for the achievement of these objectives and the need for sacrificial victims if a final victory over enemies is to be achieved.

In the course of ‘the Bolotnaya case’ (the criminal prosecution of several dozen participants of oppositionist demonstrations in Bolotnaya Square, in Moscow, the night before the presidential inauguration in May 2012), the Putin regime shifted to a policy of terrorising dissenters directly. The verdicts in the Bolotnaya case (two to three years imprisonment) demonstrated the increasing degree to which fear was being used by the Kremlin as a tool of internal policy. In this context, the image of Stalin shelters the image of a terrifying, ruthless power which invokes fear that has been passed down the generations. In this context, it proves indispensable when any moral opposition to the present regime needs to be suppressed.

Although sociologists noted the increasingly positive attitudes to Stalin back in the early 2000s, Russian intervention in Crimea brought about a qualitative change in public perceptions of his historical role. Between 2012 and 2015, the proportion of Russians who felt that great aims justified the number of Soviet people victimised during the Stalin era, rose almost twofold – from 25 per cent to 45 per cent. In August 2007, 72 per cent of respondents were willing to call the Stalinist repressions an unjustifiable political crime, but in March 2016 only 45 per cent agreed that this was true. According to a survey by the Levada Centre in February 2017, the number of Russians sympathizing with Stalin as a historical leader had reached 46 per cent – the highest level in sixteen years.

The revival of ideology

The annexation of Crimea and military aggression in the Donbass region has provoked a confrontation between the Russian state and the global community. This situation has brought about qualitative change in foreign, as well as internal, policies and led to the construction of foundations to underpin a pre-existing ideology, which has in fact been active in Russia for some time.

This includes: the image of an enemy, the contraposition of ‘us’ and ‘them’, a militarism vindicated by victory in the Second World War, a vision of the past as a heroic myth, and conflict with those who interpret the past ‘incorrectly’. In this context, the image of Stalin is skilfully exploited by the Kremlin to legitimise arbitrary state control, great-power expansionism, and policies that induce a fear of the state.

Although, in Russia, ideology is often still understood as a package of prohibitive measures, the revival of ideology is evidence of the ever more totalitarian character of Vladimir Putin’s regime.

This article was enabled with the support of the S. Fischer Stiftung.

See also: Debates on Europe series, created by S. Fischer Foundation, the German Academy of Language and Literature, and Allianz Cultural Foundation, in cooperation with Eurozine. The topic of the series is “Neighbourhood in Europe: Prospects of a common future”. The St. Petersburg Debate on Europe took place from 15 to 18 May 2016, with public sessions on the evening of 17 May.