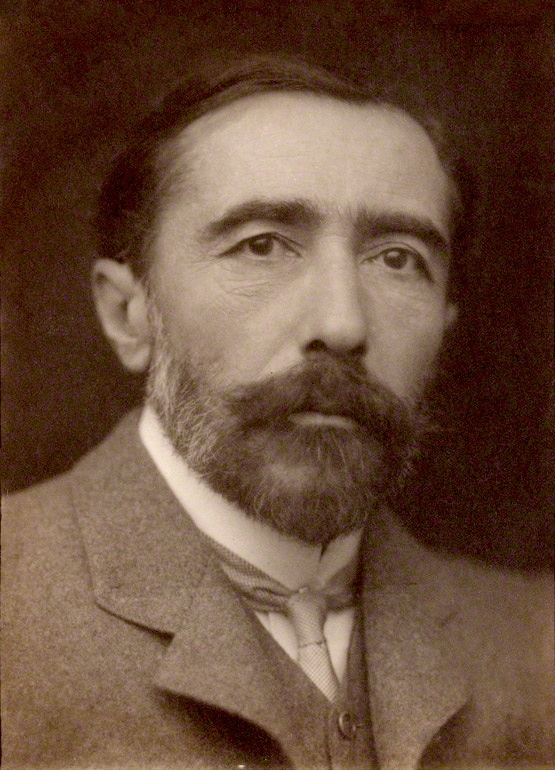

Before he ever left home, Joseph Conrad knew what powerful nations and material interests could do to weaker peoples. Born Józef Teodor Konrad Nałęcz Korzeniowski, in Berdychiv in modern-day Ukraine in 1857, he belonged to a nation, Poland, which was no longer to be found on the map. His father Apollo, a writer and prominent Polish nationalist, was arrested and exiled with his family for anti-Russian conspiracy when his son was four years old. This was Conrad’s first lesson in the power of empires and the cost of idealism. Life was difficult and by the time he was 11, both his parents were dead. Conrad never forgave imperial Russia: ‘from the very inception of her being’, he was to write in 1905, ‘the brutal destruction of dignity, of truth, of rectitude, of all that is faithful in human nature has been made the imperative condition of her existence.’ At age 17, the young Korzeniowski went to sea, serving first as an ordinary seaman and later as a ship’s officer, mostly in vessels of the British merchant marine. He learnt English in his 20s and developed an ambition to become a writer in this, his third language.

Photo: Australian National Maritime Museum. Source: Flickr

In retrospect

His first book, Almayer’s Folly, was published in 1895 under the anglicised name of Joseph Conrad. For some time he continued his career at sea before devoting himself full-time to writing. He wrote slowly, constantly struggling with deadlines and anxious about money, his work frequently interrupted by agonising periods of writer’s block and persistent illnesses. He did not achieve commercial success until late in his career. Conrad went on to write some 20 novels as well as some of the world’s greatest short fiction. Much of this work drew on places and people he had encountered during his voyages. At the end of his career, he told an interviewer that he simply wrote ‘in retrospect of what he saw and learnt during the first 35 years of his life.’

Most of the atlas of the world Conrad travelled as a sailor was marked in the colours of competing empires – British, French, Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish, Austro-Hungarian, German, Russian or Ottoman (there were also emperors in China and Japan). He sailed the Mediterranean and the Caribbean and was briefly a riverboat captain on the Congo river, working for the infamously rapacious Société Anonyme Belge pour le Commerce du Haut-Congo – an experience captured in his most famous tale Heart of Darkness (1899).

Yet his journeys often took him East, to the Malay archipelago, the Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia) and Australia. Neither a colonial official nor a ‘planter’ and certainly not a missionary, Conrad’s detached and indeed marginal point of observation as a mariner gave him a valuable perspective on the East in the age of empires. It was not a pretty sight, for the most part.

Conrad had become a naturalised British subject in 1886 and was loyal to his adopted country. For this

reason, and no doubt in deference to his English readership, he often exempts the British from his criticism of European colonial and commercial practices. Still, at the beginning of Heart of Darkness, there is a description of London, the heart of the empire, as ‘one of the dark places of the earth’, a brooding and malignant agency spreading grasping tentacles across the globe. In the same tale Marlow, a recurring character and commentator in several stories, gives his verdict on the global successes of the European empires at the end of the 19th century. ‘The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much.’

Mission civilisatrice

Few people were looking into it as closely as Joseph Conrad. Liberal statesmen like W. E. Gladstone might harbour doubts about the expansion of empire, but it seemed to have a momentum of its own, carried along by the tides of commercial, industrial and increasingly global capitalism. For the British it had always been more about trade than about political or cultural dominance and they acquired an empire not deliberately but, in the cynical words of historian J. R. Seeley, ‘in a fit of absence of mind’. Most people in Britain, as the imperialist Rudyard Kipling complained, knew little about their empire. Its economic benefits were appreciated (and probably exaggerated) and for most Englishmen it seemed natural and right that such an advanced people should find themselves in control of large numbers of inhabitants of the other side of the planet who were less developed, less modern and less able to look after themselves.

A version of Social Darwinism persuaded some that Oriental peoples were in a state of a kind of infancy, historically backward, even genetically inferior. This mindset, influentially analysed by the Palestinian-American scholar Edward W. Said in Orientalism (1978), was for most people a loose set of assumptions and prejudices rather than a thought-out political philosophy, but it seemed to others a sufficient justification for imperial activity. Besides being profitable, empire could be seen as a way of doing good, conferring on simple and benighted people the benefits of modernity, like medicine and good government, and perhaps a glimpse of higher things – the mission civilisatrice.

The focus of Conrad’s tales of the East – and this is true of the literature of colonialism in general – is predominantly on Europeans. There are some striking portraits of ‘Oriental’ characters like the splendid Malay chief in Karain: A Memory, but for the most part they are subordinate or background figures in a scene where a Western drama – tragic, comic or satirical – is played out. This is indeed the theme of the love story at the centre of Lord Jim (1900), where the quixotic young English protagonist, after a series of failures earlier in his career, seeks to redeem himself in the remote outpost of Patusan, in Sumatra or perhaps Borneo, where he has been sent as the agent of a European trading company and where he assumes a kind of leadership role for the local people.

Patusan is a stage for the performance of Jim’s drama. (It is partly, of course, a racial drama. He is often portrayed dressed in dazzling white against a dark background.) Jim regains his self-esteem, lording it over this isolated settlement and basking in the admiration of its people. His taking responsibility for them and their trust in him are symbolised in the relationship he forms with a beautiful Eurasian girl whom he names Jewel. Like the people of Patusan, she looks up to this glamorous foreigner, and he assures her he will never leave her. But in the climax of the story, when Patusan is threatened by a band of European pirates, Jim’s divided racial loyalty leads him to another catastrophic error of judgement, and Patusan and Jewel pay the price of trusting their future to him. Lord Jim is not a story about the wickedness of colonialism so much as about its egotism. For Jim, his protection of Patusan and the love of Jewel are opportunities: both are ways of reflecting his heroic conception of himself, though this unwittingly brings disaster to all of them. He loves Jewel for her alluring exoticism – though she is part European – and treats her as he might treat a child, while the name he gives her also suggests she is his vaunted possession. In Said’s terms, she is his Orient.

Ideal of work

Besides the pioneers, the leaders, the criminals and the visionaries, like Lingard in his Malay trilogy or indeed Kurtz in Heart of Darkness, Conrad was interested in what might be called the executive personnel of empire, the dogged ancillary workers who brought the mail, replenished the stores, serviced the transport and so on. As a working sailor, for him a ship’s crew was in some ways an ideal of labour and indeed of community. In The End of the Tether (1902), there is a poignant portrait of the elderly and half-blind Captain Whalley, a skipper of a steamship plying the Sumatra coast. For many voyages, his working partnership with the taciturn Malay serang or boatswain has ensured the ship’s safety and reliability. But this interracial partnership too is compromised: needing to keep earning money, unable to retire, Whalley keeps secret his encroaching blindness and the subsequent wreck is inevitable.

All across the world, Conrad saw and admired people who got on with the job, even though he suspected their ideal of service rested on allegiance to fine notions that were not grounded in reality. For such people, work was a way of not thinking about the motives and methods of the imperial enterprise they served. ‘When you have to attend to things of that sort,’ says Marlow in Heart of Darkness, ‘to the mere incidents of the surface, the reality – the reality, I tell you – fades. The inner truth is hidden – luckily, luckily’.

Typhoon (1902) is an exciting story about a ship caught in a storm in the South China Sea. It shows the unglamorous heroism of the crew, battling the huge seas in this terrifying ordeal; as so often in Conrad, the East poses a test for Europeans, exposing their qualities, good or bad. The British sailors do well in Typhoon. But they faced the test in the first place only because the pig-headed Captain MacWhirr decided, in order to save coal, to sail straight into the coming storm instead of plotting a longer course around it. Meanwhile the ship’s ‘cargo’, two hundred Chinese coolies returning home after years of indentured labour, are locked in their between-deck quarters and flung about for many hours, with their meagre belongings, vomiting and fighting in pitch darkness while the ship plunges through the storm. At the end of the voyage MacWhirr delivers them to their destination, a cargo intact, if traumatised.

Chronicler of a divided world

We learn far more from Conrad than we do, for example, from Kipling, about the economic realities of European imperialism. Heart of Darkness is about harvesting ivory and, it is more than hinted, slaves in Central Africa. The history of the imaginary South American Republic of Costaguana, in Conrad’s most ambitious novel Nostromo (1904), is a struggle for control of a natural resource, the San Tomé silver mine. Not all commercial ventures were successful, to be sure. Axel Heyst, the Swedish protagonist of Victory (1915), lives alone with one Chinese servant on a remote island in the Java Sea, surrounded by the decaying amenities of the bankrupt Tropical Belt Coal Company, which had envisaged the island as the central station of a vast commercial empire. Ironically, the island is invaded by a band of desperadoes on the basis of a false rumour that it contains untold treasure.

The piratical invaders of Victory are among Conrad’s most spectacular villains – the diabolical and woman-hating Mr Jones, his sadistic ‘secretary’ Ricardo, and the ape-like enforcer, Pedro. Heyst recognises these three rapacious emissaries from the world beyond, a world he himself had tried to leave behind. ‘Here they are, the envoys of the outer world. Here they are before you – evil intelligence, instinctive savagery, arm in arm. The brute force is at the back.’

But in truth the invasion of the sequestered island had begun with the arrival of the Tropical Belt Coal Company. Sensing the danger to come, Heyst’s Chinese servant Wang takes refuge with the Alfuro natives of the island’s interior and will neither return nor help.

It is one Eastern solution to entanglement in imported Western problems. There is little in Conrad’s fiction about the kind of anti-colonial resistance that postcolonial criticism likes to highlight. Most of the time, local people keep their heads down, get on with the job, and move out of the way if they can.

Conrad’s first empire, that of the Romanovs, wiped his country off the map and destroyed his family. The business of the European empires in the East, and elsewhere, enabled him to earn a living as a young man and later provided his writer’s memory and imagination with a lifetime of material. Empire, and the idea of Orientalism that underwrote it, enlarged the difference between people, the colonisers and colonised, West and East. Conrad is one of the great chroniclers of this divided, bifurcated, unequal world. But like any great writer, he produced a fiction which also could not help showing what all people have in common. ‘Why,’ he wondered in A Personal Record (1912), ‘should the memory of these beings, seen in their obscure sun-bathed existence, demand to express itself in the shape of a novel, except on the ground of that mysterious fellowship which unites in a community of hopes and fears all the dwellers on this earth?’