Russia’s younger generation have failed to build upon the democratic achievements of their predecessors of the 1990s. Surveys show a reversion to Soviet-era conformism, whether as passivity and cynicism, or individualism and status obsession.

At the beginning of the 1990s, prospects for modernisation and democratic change in Russian society were linked to the younger generation. Sociologists identified the bearers of new values not only in the educated classes, or in the modern, more complex social environment of large cities and megacities, but first and foremost amongst the youth. At the beginning of the 1990s, young people stood out from other generations for their inclination towards liberal-democratic values, civil rights and freedom, their openness towards the West and their attitude towards social achievement and success. Even at the start of the economic reforms, when – after a short period of euphoric expectation that things would rapidly change for the better – the majority of the population was plunged into a state of frustration and confusion and increasingly took the view that any changes in the country were imposed from above, young people demonstrated a more positive attitude and were more content with their own lives.

Hopes that young people would be able to quickly adopt western ideas and democratic principles were also characteristic of the liberal and democratic parties and social movements of the 1990s. Ideas about how Russian society and its economy might be modernized emerged directly from the educated classes – primarily residents of large cities and youth – and involved complex ideas of justice, human rights, a democratic state, the independence of the judiciary, the protection of private property and so on. These social environments were expected to encourage the institutional consolidation of the values of democratic rule-of-law state, civil rights and freedoms and the displacement of former Soviet stereotypes and complexes. The new opinions expressed by youth and other socio-demographic groups, which were clearly recorded in polls conducted by the Levada Center, were interpreted as evidence of changes taking place in society. Indeed, in the early 1990s, the polling responses from young people differed to the general population, suggesting an allegiance to democratic rights and freedoms and endorsement of the values of economic liberalism, success and achievement, as well as a greater openness towards the West.

By the mid-1990s, however it became apparent that it had been wishful thinking to describe the younger generation as modernisers and bearers of new liberal democratic values that were devoted to the western political and economic model. Comparative analysis of data on generations revealed that the “pro-Western” orientations of young people were mostly declarative and unstable. In other words, as they mature, young people increasingly fit into the structure of basic values still connected with the Soviet past. The general negative sentiment that prevailed in public opinion right up to the early 2000s only increased adolescents’ susceptibility towards typical complexes, stereotypes and prejudices inherent in the Soviet Union. In the 1990s, the Soviet period was still positively mythologised in the public consciousness, as if this was a massive traumatic reaction to the disintegration of the USSR and the consequences of the radical reforms. These sentiments were picked up by the reoriented media and later reflected in official rhetoric.

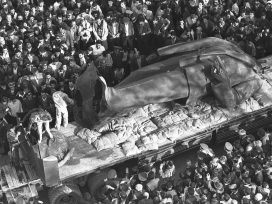

Source: Flickr

Two generations of post-Soviets

Most people perceived the changes of the 1990s as forced, imposed, incomprehensible and lacking in positive goals. This determined people’s most common type of adaptation – namely downwards adaptation, which amounted to a struggle for survival. Roughly speaking, only one-tenth of all respondents felt that the changes opened up new opportunities for using their strengths and abilities for personal development and success. This meant that, on the whole, short-lived hopes for rapid, large-scale improvements were replaced by much more limited aspirations concerning the resolution of everyday, routine problems.

Most people survived the dramatic changes of the 1990s by turning to Soviet ideas, proclivities and behavioural patterns. The elites were weak and unprepared for serious social and political transformations and failed to implement democratic reforms in politics and the public sphere. In most people’s eyes, the state consigned its citizens to their fate. The only experience that the generation of “parents” was able to pass on to their children in this era of change was that of individual survival and passive adaptation. In post-Soviet society, unlike in the West, a value-based conflict of generations never arose. A “working through” of such a conflict could have become a means of genuine social transformation. But all manner of problems inherited from the Soviet past remained unreflected, which made the alteration of Soviet mentality difficult.

The collapse of the Soviet institutional system, meant that the welfare state ceased to function; that educational, healthcare, science and media institutions deteriorated; that power became increasingly arbitrary and that corruption increased; and that the legal system and courts became more and more reliant on the authorities. Under these conditions, a significant responsibility for the new generation’s socialization and adaptation to the changing reality fell on the family. One of the family’s main challenges was to ensure the possibility of a “better life” for children. At the same time, the passive adaptation to changes by “adults” themselves, by lowering their own demands and expectations, led to a general narrowing and simplification of the notion of “the future” and a focus on everyday problems. The wellbeing of children was, as many years of polling have shown, seen as compensation for what generations of parents felt they had lacked in terms of material security and relative freedom from everyday burdens.

Values, self-perceptions, prospects

Surveys of young people in the mid-2000s and 2010s show that youngsters growing up in the post-Soviet period tended to regard personal success (understood primarily as material wellbeing and status) as a priority and to seek entry into the power hierarchy, but cared little about social recognition of personal achievements, the desire for self-improvement, social and civic responsibility and political participation.

According to surveys of urban youth conducted in the 2000s, the overwhelming majority (as much as four-fifths) believed that they had already been successful in life. Given the uncertain future for the majority of young people, one needs to bear in mind that the notion of “success” in the youth environment is associated not so much with real achievements as with self-identification. “Success” in this context is nothing more than a sign of belonging to a collective “we”, those who are alright. There is an overriding opinion that in order to achieve success one needs help and support from influential people (the equivalent of the Soviet “blat” – “old boys” network). Moreover, instrumental and immoral activity is regarded as something good in order to achieve one’s goal.

In the list of qualities that ensure success, young people place “ambition” and “assertiveness” – those qualities crucial for someone career-oriented – fairly low down. These were traditionally perceived as negative in paternalistic and egalitarian-collectivist Soviet society and today are still seen with suspicion. Young people, especially among the least adapted sections of society, put a greater emphasis on external factors of success (such as support networks) and at the same time see “successful people” negatively and with envy. The very fact that young people list, as important requirements for success, phenomena usually evaluated negatively in mass consciousness – old boys networks, the use of power, connections, cynicism, selfish calculation, pragmatism – testify to a decline in the value of professional success as such. Young people’s view of the requirements for achieving success morally justifies a passive attitude and prevents them from striving for more or from building a career, since the aforementioned means are unsuitable for an “honest person”.

It is worth noting that young people have no clear idea of a “big” future, despite their confidence in their own situation, their satisfaction with life and their high opinion of their own success. Polls have shown that about 80 per cent of Russians have no long-term plans. Even by the end of the “prosperous” first decade of this century, the majority of young people in cities believed that they could plan their lives no more than a year or two ahead. Long term planning of the future remained important only among groups of young people who, for professional reasons, are included in social contexts that involve more complex interaction.

This indifference concerning one’s own future (combined with satisfaction with one’s own life and “achievements”) can be seen as an attitude inherited from the parents’ generation, whose dependence on the Soviet system was accompanied by a strong feeing of lacking perspectives and control over one’s own life. It is no coincidence that, even among the most prosperous and successful young people, the majority admit that they cannot (and do not want to) change the political situation, that they are unable to defend their rights, and that they are incapable of opposing the arbitrariness of power.

Career, status, aspiration

Over the past twenty years, young people have not only demonstrated their preference for western forms of entertainment, but also have high income expectations. Requests for high entry salaries are often incommensurate with their real knowledge, skills and abilities. The majority of respondents consider higher education vital for a successful career. A significant number of young people believe that a formal qualification alone will open the door to high earnings. The specific preparation for a future profession is often seen as less important than the diploma itself. Students typically have very vague ideas about their future professions. Studies show that up to two-fifths do not plan to work in the profession in which they are being trained. For most young people, acquiring further knowledge of their respective profession after completing their degree seems unimportant; they prefer to break into established economic niches where there is “big money”. For these reasons, individual achievement and personal endeavour are devalued in education.

Another trend is the growing tendency towards western levels of expenditure on costly, modern leisure activities. Mainly young and fairly well-to-do people take part in such urban leisure and entertainment activities; most older adults are satisfied with “domestic” ways of spending their free time – watching television and videos; carrying out household tasks or communicating with neighbours and relatives. Since the majority of young people – including those that are married, which is on average 70 per cent of young respondents – live with their parents or other relatives, we can assume that they run a common household with them. And since young people, especially those living in big cities, are expressly geared towards spending money on boosting their “status” and modern leisure activities, this sows the seeds for a generational conflict and an increase in internal tensions and mutual misunderstanding.

The origins of the youth’s disregard of everyday “adult” concerns lies in Soviet “child-centrism” and its consequences. Parents’ discontent with and resentment of their children, which sociologists capture in the data, also demonstrates a lack of mutual understanding between the generations. Most parents of young adults have an almost neurotic notion of “life for the sake of children”. This self-sacrificing attitude among the Soviet generation of parents is linked to the survival of the attitude described above. The parents’ generation has made an enormous effort to maintain a “normal life” for their family and children in order “to help them on in life”, but this sacrifice is not necessarily appreciated by their children, who often see it as something that should just happen naturally.

Thus, over the past two decades, young people, especially those living in large cities, have adapted relatively quickly to social and political changes, and have distinguished themselves from the disoriented masses (whose dissatisfaction is exploited politically by the left or a national-patriotic parties). Over time, young people, who in the early 1990s were seen as the bearers of new values, began to consider themselves as a special, more valuable group than other generations, while not showing any special achievements in social, civil or political life. Rather, they saw their “privileged” position as something natural, having received freedom and opportunities in a “readymade” form that had not been available to older people. Freedom was therefore treated by them not as a value, but as a given. Hence the younger generation, as the Russian society in general, failed to adopt the new ideas and values necessary for democratization and modernization.

Politics

Until around 1998, the overall political climate in Russia remained relatively liberal and the plurality of opinion persisted. During that period, young people’s political positions were fairly outspoken and polarised: they were ready to support both liberal, pro-western parties and rightwing nationalist politicians such as Vladimir Zhirinovsky. (The latter was initially supported by the down-and-out youth in small depressed towns.) Over time, however, the popularity of liberal politicians fell and public criticism of the Soviet system was practically forgotten by a society preoccupied with the problems of everyday survival.

Since the late 1990s, with the strengthening of authoritarianism, the control of power over the media, the decline of democratic institutions and rising corruption in society, the role of specific, pre-modern, traditional values has increased. There has been a massive rise in archaic, traditionalist sentiments, and the political instrumentalisation of such sentiments by the Kremlin. There has been an increase in support for “Putin’s power hierarchy”, primarily amongst young people – i.e. those who are “cut off from the past” and who isolate themselves from politics.

In the early 2000s, young people, like the other generations, generally accepted the creation of an external enemy – a hostile and mercenary West – brought back from the Soviet past without much resistance. The concept of the besieged fortress became the basis for negative mass mobilisation. This was accompanied by the exclusion of young people from the public sphere and by the decreasing importance of alternative positions among different political groups, of expert opinions and of public criticism of the authorities. There was a mass anti-westernism of the young, and, to an even greater extent anti-Americanism; mass xenophobia combined with the growth of Russian nationalism. The revival of great power sentiments is combined with an ostentatious “westernisation” among the most successful, wealthy and adapted urban youth. This group demonstrate new standards of consumption and modern forms of entertainment and leisure, which, as before, are unavailable to the overwhelming majority of young people.

Russia’s youth cannot be called completely apolitical. Young people follow politics no less than older generations, and use more diverse channels of information – the internet, and in recent years, social networks. But only a minority use alternative sources of information in order to develop their own assessment of current affairs. For young people, like most of the population, it is normal to take on the position of a passive spectator who prefers to take on trust what national media or tabloids offer them.

In general, the last ten years of surveys indicate a declining interest in and growing ignorance about politics among young people. This pertains particularly to information provided by independent media that interpret events in Russia and the world from democratic and liberal positions, a development that could already be observed after the suppressed protests between 2011 and 2013, and that became obvious after the annexation of Crimea and the beginning of the war in the Donbas. Even when, during the aforementioned political protests, a string of repressive laws were adopted that aimed at suppressing civil and political activities, only around a third of young people surveyed were critical. Finally, after the annexation of Crimea, there was almost universal, unanimous approval of the regime’s actions, not only against external enemies, but also against internal enemies known to “rock the boat”. Russian society and its youth faction, having previously refused to actively participate in political life, fast became a fertile breeding ground for patriotic propaganda about Russia as a “great power”.

Today, the majority of young people in Russia represent the most passive group in terms of political participation – no more than 4 to 5 per cent of young people under 24 are socially and civically active. Of course, this development started earlier. In the 2000s, sociologists observed among 20 and 30-year-olds a significant decline in interest in political events in both the country and the world and a growing lack of interest in the history of Russia, especially in relation to the changes in the 1980s and 1990s. Democratic or liberal positions also started to become marginalised. Differences between political positions narrowed, political choice was typically rejected and the values of solidarity and compassion were replaced by cynicism.

Attitudes towards the Orange Revolution in Ukraine are telling of Russian youth in the first decade of this century. More than a third (37 per cent) of young people surveyed in 2005 followed the events that unfolded on Kiev’s Maidan square. Among them, 24 per cent believed that the protests did Ukraine neither harm nor good and 25 per cent found it difficult to formulate an opinion on this subject. Only 3 per cent of young respondents agreed that the protests “were very useful for Ukraine”. This means that half of the young people following the events in Ukraine saw no “meaning” in them and developed no independent assessment of such an important event in the post-Soviet space. The most popular answer to the question of the protesters’ motives at that time was that “the participants were paid money”. This motive was cited by 52 per cent of young people (another 25 per cent considered this the second most important motive). They thereby followed the explanation that had been spun by political strategists in the Kremlin. Idealistic motives were considered most important by only 30 per cent of young people following the events. The hypertrophied fears of the Russian authorities regarding the “orange threat”, however, seemed unfounded: 72 per cent of young respondents “definitely would not like it” if the “Orange Revolution” were to take place in Russia.

It was important for the Kremlin to support the cynical and indifferent reaction of the majority of young people. Against this backdrop, anti-orange performances by the “Nashi” youth movement became acceptable. After the victory of the second Maidan protest, an aggressive anti-Ukraine campaign was unleashed on an unprecedented scale. Amidst the general anti-Ukrainian hysteria, young people differ from other respondents only by their greater tendency to skip certain answers related to the annexation of Crimea and the Russo-Ukrainian war in the Donbas, while at the same time mirroring the majority of the population in their almost universal approval of the Kremlin’s actions in Ukraine.

The exception to the trend

The generation of young people who grew up in the Putin era is a generation without a memory, which accepts, without much resistance, ideological interpretations of recent Soviet history, as dictated by the regime and supplied by its media. The youth milieu lacks incentives for understanding and carrying out productive criticism of the democratic changes that occurred in the 1990s. Today, 90 per cent of young people do not know about the August Coup of 1991 and the victory of the democrats, which was backed by the overwhelming majority of the population. A significant number have no opinion about the events that took place in the 1990s, about the Soviet era or the crimes that occurred under Stalin.

A generation has grown up accustomed to thinking the same as the majority of the population. Today, this manifests itself most keenly in the overwhelming support for the president (as manifested by the expression “Putin’s youth”), for the ruling United Russia party, and for the authorities more generally. Such strong support for the political regime among young people (here we’re talking 18–24 year-olds) is concomitant with the lowest level of political participation of all generations.

Nevertheless, a democratically and liberally-minded minority of young people does exist, especially in large cities (according to our estimates, it is between 5 and 7 per cent). These are the most educated, qualified, successful members of that generation, who demonstrate a responsible and active civil position in relation to events in Russia. It is in this environment that the idea of a common social good is beginning to emerge, evoking an interest and sympathy for socially disadvantaged groups, which in turn has led to various civil initiatives and voluntary movements.

It was this milieu that largely triggered the 2011–2013 protest movement, in response to massive fraud in the Duma elections. The fraud was revealed by a self-organized group of observers largely made up of young people. However, from rally to rally, the participation of young protesters has decreased. The Levada Center’s surveys on the “Bolotnaya Square case” showed that the age composition of the participants is increasingly approaching the average. Young people in the towns and cities were the catalyst that ignited the protests, but their activities did not translate into broad youth movements. It seems particularly significant when comparing protests in Russia with events in Ukraine that there was no mass participation of students in the former. The repressive political regime quickly deprived youth protests of their energy and plunged the liberal-minded part of society into a state of growing apathy and demoralisation.

Moscow, February 2017

Postscript

On 26 March 2017, after this article was written, a new wave of protests against corruption in the Russian government swept through many Russian cities. Triggered by an investigative video about Medvedev’s secret assets in Russia and abroad, published on YouTube by Alexei Navalny’s Foundation for Fighting Corruption, the protests attracted an unusually high number of youth. They included not only university but also high school students. These young people, born during the Putin era and subjected to “patriotic education” in schools, caught sociologists by surprise. The phenomenon was explained with the use of social networks and the innovative mobilization strategies of Navalny and his team. It remains to be seen if the protests will continue. While the pro-Putin majority among the younger generation and in Russian society in general is unlikely to be challenged in the near future, tensions are also likely to rise. Politically engaged small groups of young people can potentially become an agent of change after all.

Published 7 June 2017

Original in Russian

Translated by

Ruth Green

First published by Eurozine (English version)

© Natalia Zorkaya / IWM / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Russia’s orbit

Osteuropa 4/2024

Repression, murder, war: on the logic driving the Putin regime toward ever-greater excesses of violence. Featuring Yuri Andrukhovych on the Russian colonial empire – the only ever to have tried to reconquer a former possession. Also: articles on Navalny, and on what next for Georgia?

Turkey is no longer a dissident safe haven. High-profile cases of outspoken exiles kidnapped or even killed by spies when in the country attest to the risks. Interviews with Iranian and Russian exiles reveal deteriorating circumstances, from visa refusal to societal racism, police persecution and serious abduction threats, exposing uncertain, shifting political ground.