The new European debate on laws, borders and human rights was the subject of this year’s Eurozine conference, held in Conversano from 3 to 6 October, and co-organized by La Fondazione Giuseppe Di Vagno and Eurozine partner journal Lettera internazionale.

Under the heading “Law and Border – House Search in Fortress Europe”, this year’s Eurozine conference addressed the EU’s refugee and immigration policies. More than 100 editors and intellectuals from Europe’s leading cultural journals participated in the event.

On 3 October 2013, over 360 men, women and children drowned off the coast of Lampedusa attempting to enter Europe. At the time, Italian president Giorgio Napolitano lamented the “slaughter of innocents” and the tragic event – one of many at the gates of Fortress Europe – triggered a new European debate on laws, borders and human rights.

Exactly one year after the Lampedusa shipwreck, the conference continued this debate, drawing on the fact that Eurozine is a transnational network, representing views and experiences from all parts of Europe – and beyond. The renewed focus on migrants landing on Europe’s Mediterranean shores has added to the difference of perspectives between southern and northern EU countries, which first surfaced with the economic crisis in 2008. Many southern frontier member states – Italy included – feel that they are being left alone to deal with the economic, legal and moral challenges, which come with refugees and asylum seekers. At the same time, the tensions between western and eastern Europe have never left the agenda. Populist politics demonizes immigrants per se; the most recent occasion for xenophobic rhetoric being the lifting of work restrictions on Romanians and Bulgarians earlier this year. There is a fortress within the fortress.

This year’s meeting was organized by the European network of cultural journals, Eurozine, in cooperation with La Fondazione Giuseppe Di Vagno and Eurozine partner journal Lettera internazionale.

Cesare Preti, philosophy teacher and member of the advisory board of La Fondazione Giuseppe Di Vagno, presents material from the foundation’s archives. Photo: Nadine Blanchard

In a pre-conference presentation on Thursday evening at La Fondazione Giuseppe Di Vagno (1889-1921), Cesare Preti presented documents from the foundation’s archives. Giuseppe Di Vagno was the first Italian parliamentarian to be killed by the Fascists, as conveyed in Pierluigi Ferrandini’s film Lutto di civiltá, screened at the end of the presentation. A growing number of multimedia materials from the archives, which span a period that begins with Di Vagno’s lifetime and extends to the present day, are available online via the digital portal Memoria Democratica Pugliese.

Auditorium San Giuseppe. Photo: Mattia Ramunni

Friday 3 October: An opening evening between past and present

Inaugural speeches by the conference organizers and the keynote by Italian historian of political ideas Carlo Galli, simply entitled “1814-1914-2014”, were delivered on Friday evening at Auditorium San Giuseppe, a deconsecrated seventeenth-century church.

Carlo Galli. Photo: Mattia Ramunni

Here, as in all the conference venues, interventions by creative director Annalisa Simone provided a connective tissue between and around the main conference content: in this case, in the form of pallets used for transporting goods, piled up to create the stage on which ensuing conference sessions took place. Without a word having been said, the structure immediately suggested that the free movement of goods did not necessarily sit comfortably with the free movement of people, as the piles of pallets took on the form not just of a stage but of a makeshift barrier too.

Eurozine editor-in-chief Carl Henrik Fredriksson prefaced Galli’s speech by drawing attention to how the security doctrine agreed in 1814 sacrificed the real needs of regions in the name of preserving the balance of power in Europe. Defining some countries purely as buffer zones may have seemed expedient at the time but social upheaval had recurred throughout Europe by 1848. Fredriksson implied that, where buffer zones, protest, oppression and revolution are concerned, similar dynamics may well currently be at play in Ukraine – where to date over 3000 people have died in the crisis, roughly the same number of people as had perished in the Mediterranean at the gates of Fortress Europe in 2014. But, Fredriksson concluded, the aim of the Eurozine conference was to go beyond the figures reported on a daily basis and take a deeper look at the issues.

Carl Henrik Fredriksson. Photo: Mattia Ramunni

Biancamaria Bruno, editor-in-chief of Lettera internazionale, stressed that there had never been a more pressing need for the Eurozine network meeting in Italy, given that the country now faced sharing the fate of too many cultural institutions in Europe: that of being cast aside and left isolated. Bruno was pleased to announce that the thirtieth birthday of her publication, itself part of a Lettera journal network spanning several European countries, coincided with the conference, making Lettera internazionale more determined than ever to continue its struggle against “the provincialism of the great European cultures”.

Biancamaria Bruno. Photo: Mattia Ramunni

Bruno went on to state that Mare Nostrum, the Italian Mediterranean naval operation established in the wake of the Lampedusa shipwreck on 3 October 2013 and which has since rescued tens of thousands of refugees and migrants, was certainly necessary. But she was sceptical about whether it could solve a problem linked directly to western foreign and development policies.

Filippo Gianuzzi, programme director at La Fondazione Giuseppe Di Vagno, emphasized that questions of identity and cooperation go hand-in-hand, asking what culture can do to prompt genuine critical thinking. This being key, he said, to entering a realm beyond the special effects of European policy-making, in order to refrain once and for all from robbing migrants of their dignity.

Filippo Gianuzzi. Photo: Mattia Ramunni

Finally, Carlo Galli broached the theme of Fortress Europe in terms of the external manifestation of internal weaknesses. Internal ruptures are far from new in Europe. The sustained exclusion and, ultimately, the attempted annihilation of Jews, as well as the continuous rejection of Muslims: these phenomena have left behind the scars of inner turmoil. As have the protracted clashes between the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy that ultimately gave way to World War I, in which European civilizations realized that they were mortal too, just like the others.

Indeed, the trenches a century ago can be compared directly to the Mediterranean border, said Galli: both are the results of European contradictions. That migrants perish at the gates of Fortress Europe is a symptom of a global disorder in which Europe has become a passive player. Meanwhile, the discrimination against those who gain entry is hardly helped by the absence of common social and economic policies. A single currency, moreover, only creates further conflict; aggressive forms of nationalism return. “It is time to focus on ourselves”, Galli concluded, “and how we talk about the other”.

Gianvito Mastroleo, president of La Fondazione Giuseppi Di Vagno, and mayor of Conversano, Giuseppe Lovascio, welcome reception, Pinacoteca Comunale di Conversano. Photo: Nadine Blanchard

Conference participants then crossed Conversano’s main piazza to the Pinacoteca in the castle, to be received by Gianvito Mastroleo, president of La Fondazione Giuseppi Di Vagno. In the midst of Paolo Finoglio’s early baroque cycle of paintings depicting Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata (Jerusalem Delivered), Mastroleo spoke of the foundation’s Lector in Fabula literary festival, one of the most important in southern Italy. The dream encapsulated in the festival was, he said, “not to teach but to learn.” Mastroleo hoped that the Eurozine conference, which opened shortly after the festival, would continue in the same spirit – a prospect assured by the assistance of the outstanding Lector in Fabula team. Mastroleo also outlined the aims of the foundation as an organization independent of political parties but close to politics: to elaborate individual and collective rights always with the ideal in mind of a borderless world without conflict. The mayor of Conversano, Giuseppe Lovascio, concluded the reception by highlighting the importance of the international partnership with Eurozine for Conversano and the region of Apulia.

Fabrizio Gatti, Teatro Norba. Photo: Nadine Blanchard

The same evening, Italian investigative journalist Fabrizio Gatti mesmerized the audience at the conference’s first public event, which took place at a sold-out Teatro Norba. Based on his book Bilal and further published reportage, Gatti’s candid and energetic portrayal of “the slave route to Europe” recounted in detail some of the life stories and the terror that prefaced the deaths of at least 268 Syrian refugees as their overloaded fishing boat bound for Europe sunk on 11 October 2013.

Gatti’s presentation of the figures was equally compelling: “Take the total number of irregular migrants who have landed in Europe this year: 130,000. Then consider the total population of the European Union: around 505 million. Do the maths. Would it really be so controversial, the arrival of 130 people for every 505,000?” Only under a system of neoliberalism at home and of neo-colonialism abroad, Gatti argued – systems that are starting to alter the fabric of society in Italy too, as Italian agricultural workers now accept the miserable conditions once reserved for migrants.

It was almost midnight when Swedish poet and Glänta editor Linn Hansén entered into conversation with Gatti on the dismal “illegal” migration discourse conducted in some of the richest countries on earth. The discussion, together with Gatti’s responses to questions from the audience, reaffirmed the case for opening a humanitarian corridor to Europe.

Saturday 4 October: A day between policy and reality

It quickly became apparent in the first panel session on Saturday, entitled “Free movement vs controlled migration”, that freedom of movement had never been free from control. Taking the floor in the Auditorium San Giuseppe, speaker and French scholar of mobility Serge Weber gave a thorough account of the EU’s expensive and complicated system of migration prevention to date, a system situated on the “margins of legality” that he said suited ever-expanding security markets and creeping processes of privatization. All of which Weber considered to amount to a form of soft imperialism.

Serge Weber. Photo: Nadine Blanchard

In the ensuing panel discussion, human rights activist and founder of the Policy Centre for Roma and Minorities in Bucharest Valeriu Nicolae spoke of the European Union’s refusal to engage directly with minorities, raising the spectre of a fortress within the fortress. This in contrast to a recent film entitled Toto and His Sisters, a film that Nicolae helped produce, which documents the everyday lives of Roma people. He concluded that unless an EU watchdog were established to maintain standards, it was unlikely that the rift between policy and reality could be overcome.

Italian law scholar Angela Maria Romito alluded to the complexity of the European legal framework in freedom of movement matters, outlining the array of fora in which associated proceedings could be brought, including the European Court of Justice and European Court of Human Rights, to say nothing of more specialized infringement hearings before specially convened committees and the implications of non-binding guidelines incorporated into international law. Finally, Eve Geddie, programmes director at Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM, UK), considered the greatest threat of all to be the criminalization of migration, noting that some of her colleagues had even begun to speak of “crimmigration”. Hence an urgent need to change the discourse on “illegal” migration and use other formulations instead, such as “undocumented” or “irregular” migration.

This is an issue to which education is key, an area that several audience questions tackled. In response to which, Geddie referred to PICUM’s recent web documentary and teaching guide “Undocumentary: The Reality of Undocumented Migrants in Europe”.

Marica Di Pierri, Slavenka Drakulic, Marina Lalovic, Rita El Khayat and Silvia Godelli, Teatro Norba. Photo: Antonia Plessing

The second conference session, entitled “Mater Mediterranea”, focused on how women migrants remain especially exposed, particularly in situations of war and environmental conflict. Slavenka Drakulic talked about the use of rape as a weapon in wartime, noting that although an estimated 30 to 60,000 women were violated during the Yugoslavian wars, it was already 2002 by the time the first group of men were tried for related war crimes. Meanwhile, she insisted, a general and pervasive gender inequality makes women’s lives more perilous than men’s in many respects, whether walking past the park on the way home at night or crossing an ocean in an attempt to find a safe haven in Europe or the United States.

Silvia Godelli then revisited the formative experience of the influx of Albanians into Apulia in the 1990s. Godelli, who is the Assessor in the Apulian government responsible for the Mediterranean, culture and tourism, pointed out that the episode involved 1000s of Albanians arriving en masse. And yet, the region did not change: the Albanians spoke Italian and integrated swiftly, while the host population remained more or less oblivious as to the migrants’ native language or creed. However, the more recent arrival of 100s of Africans and Arabs has sparked a crisis of identity.

It fell to activist and journalist Marica Di Pierri to explain how women came to be on the frontline of environmental and natural resource conflicts all over the world, from dam development projects in India through the “invisible” (albeit less so now than previously) indigenous women of Latin America campaigning against neoliberalism to the victims of pollution that the chemical industry has caused just an hour away from Conversano, in Brindisi. That this is so stems from women being primarily responsible, in many such situations, for their family’s livelihoods and especially for agricultural practices, said Di Pierri. And if estimates indicating environmental migrants outnumber war refugees by a factor of four are to be believed, then this is an area in which women migrants, among others, urgently need both recognition and new regulations.

The writer, anthropologist and Nobel Peace Prize nominee Rita El Khayat changed the focus of the conversation once again. In her home country of Morocco, between 50 and 70 per cent of women remain illiterate. The main obstacle stopping women migrating is tradition. Nonetheless, male migrants in France won the right in the 1970s to receive their families from their native countries. In subsequent decades, women and children began to migrate alone. But then the veil and an assortment of other conservative traditions returned and Islamic networks throughout Europe were strengthened. Crossing certain distances became a matter of traversing several centuries.

Sunday 5 October: Visualizing the future of migration

On Sunday, photographers Giovanni Cocco and Emiliano Mancuso gave thoroughly moving tours of the conference’s multiple exhibitions, housed in the eleventh-century monastery of San Benedetto.

Cocco covered the photographic documentation of his travels, often accompanied by Fabrizio Gatti, to Europe’s peripheries, whether to the Turkish-Greek border on the river Evros, the Spanish enclave of Melilla bordering on Morocco or to the island of Lampedusa. The brutal conditions with which migrants must reckon in making the most perilous of journeys, often in order to escape some of the world’s most authoritarian regimes, recalled Gatti’s words: these stories are “beyond human imagination.”

A reading from Gatti’s works by Domenico Giannini, accompanied on the guitar by Miriam Lorusso, added a further dimension to the richly presented exhibitions, which incorporated most media forms. Mancuso then proceeded to explain that the system is based on fear and the human traffickers are akin to drug dealers: the bottom line is, you have to pay. Moreover, you have to pay several times the price of travelling legally and that’s often everything you have and more. There is no mercy. Meanwhile, the authorities squabble. Massimo Sestini’s iconic image of the overloaded boat in the shape of an arrow you may expect to see on a sign indicating a one-way street is symbolic, Mancuso explained, of a scenario that now occurs every day.

Photo: Massimo Sestini

Moreover, we all have something to do with so-called “illegal” migration, with “black” agricultural workers: in fact, they’re round the corner right now, picking the tomatoes that go into your ketchup or passata, Mancuso said – as documented by the photographer Rocco De Benedictis.

A scene from the exhibition of Rocco De Benedictis’ works, monastery of San Benedetto. Photo: Antonia Plessing

Mancuso concluded with the his own exhibition of photographs, texts and film, entitled “Felix’s diary”, which told the story of a group house in which Italian children in care found themselves living with migrant children in care: a laboratory of integration.

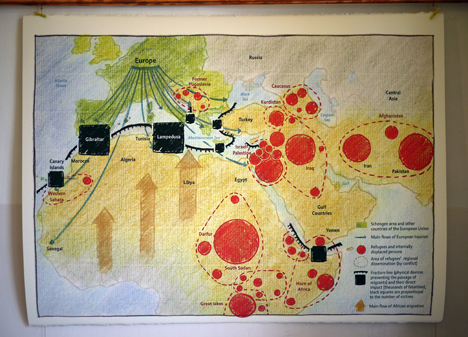

Regimes of mobility, as depicting by Philippe Rekacewicz. Photo: Antonia Plessing

These exhibitions will all be displayed in Rome later this year. Meanwhile, Philippe Rekacewicz‘s cartography will appear in Gothenburg. We’ll provide further details as soon as they’re confirmed.

Parallel Sunday afternoon workshops dealt with network-specific matters. There was a preparatory session on Eurozine’s 2015 conference, to be held in Maribor, Slovenia, a hands-on discussion about social media (a topic proposed by participants in the “print vs. digital” workshop at last year’s conference) and an exchange entitled “North and South in dialogue: Continuing Conversano”. The latter explored how cooperation with the South can be sustained through cultivating relations with initiatives such as the Time to Talk network, so that intellectuals from southern Europe are included in the discussion about European issues; establishing an Editor in Residence programme in Conversano and Rome open to editors in the Eurozine network; and various initiatives to help discover emerging talents from south-eastern Europe interested in contributing to cultural journals.

The future of migration provided the focus for the final conference panel. Swedish political scientist Peo Hansen offered an analysis of the “crisis in free movement”: the pace of migration control far outstrips any socio-economic measures to ease migration, despite leading commentators openly admitting that we need migrants to ensure our own economic survival. Thus the debate on the future of migration concerns the future of capitalism itself.

Italian sociologist Onofrio Romano discerned a fetishization of mobility in the very use of the word “migrant”, shorn of both the “e” in emigrant and the “im” in immigrant. Rather than the direction of the flow, the interest nowadays is exclusively in the migratory flow itself, which thus becomes akin to naturalized financial flows. Aided by the media landscape moulded by modernity’s “second wave”, an undifferentiated horizontalism tends to stand in for a verticalist approach that might once have provided protection against a rent on general intellect and could still yield a sovereign Mediterranean region capable of realizing the ideal of the “Greek politics”.

Peo Hansen, Sally Davison, Rita El Khayat, Onofrio Romano on “The future of migration”. Photo: Nadine Blanchard

Closing comments hinged on the need for striking up an understanding of and among peoples inhabiting utterly separate spheres, whether that be the hallowed highways of mobility or modern migrant hells, and the role of the public intellectual in cultivating such understandings, lest one and all be sacrificed to the general principle of competition. Because though neoliberal proponents of opening up all the borders may have a voice, the prospect of actually doing away with all borders is simply not on the agenda. Not least because migration can never be examined in isolation from geopolitical power relations.

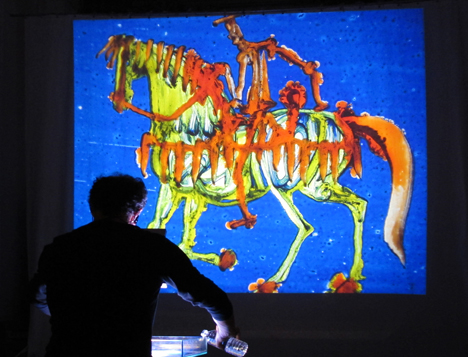

The conference closed with a riveting performance by author and illustrator Gek Tessaro in Auditorium San Giuseppe. Entitled The Heart of Quixote, Tessaro’s intervention crossed the boundaries of theatre, illustration, animation, choreography and storytelling in relating his own provocative version of Cervantes’ classic. As Tessaro both narrated the story and illustrated it live, drawing with both hands directly onto layered transparent films, his illustrations were simultaneously projected onto a giant screen. The whole performance was seamlessly choreographed to a lively soundtrack, including music by Rémy Aubry and Ivano Fossati.

Thus Quixote chooses to travel the world in search of adventure, “to avenge injustice and put all wrongs right” and yet another perilous journey begins: “And since there were so many wrongs to put right, so much abuse and injustice to avenge and evil to correct, he didn’t wait a moment longer, thinking only of how much more the world would have suffered if he had hesitated even a little.”1

Gek Tessaro’s. Photo: Nadine Blanchard

Texts based on presentations given at the 26th European meeting of cultural journals will be published in Eurozine in the coming weeks. Read all articles in the focal point: Beyond Fortress Europe.

Photographic impressions

Translation by Jonathan M.R. Cox, from Gek Tessaro's book of the same name as the performance, The Heart of Quixote, originally published as Il cuore di Chisciotte (Carthusia Edizioni, 2011).

Published 5 November 2014

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.